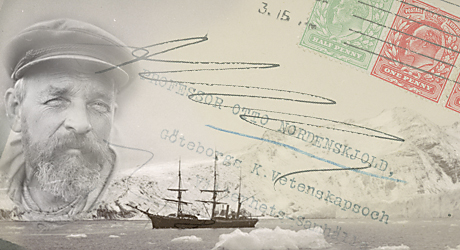

Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjöld Swedish South Polar Expedition: (1901-04)

A fictional account of Nordenskjöld’s Swedish expedition would probably be dismissed as fanciful and overladen with coincidence. The plan was simple: Antarctic, Henryk Bull’s old sealing ship, commanded by Carl Anton Larsen, was to leave Nordenskjöld and a party of scientists to explore the eastern side of the Antarctic Peninsula for a year while others on the ship conducted scientific work elsewhere before the two parties united the following summer. The leader, 32-year-old geologist Otto Nordenskjöld was the nephew of Adolf Nordenskjöld, who had discovered the Northeast Passage across the top of Siberia.

Antarctic left Gothenburg on 16 October 1901 and arrived in the South Shetland Islands in January 1902. The expedition established that Trinity Peninsula and Danco Land were part of a single peninsula, and the ship sailed between the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula and Joinville Island through a passage that Nordenskjöld named Antarctic Strait (now Antarctic Sound), after his vessel. In February 1902, Nordenskjöld’s scientific party of six landed at Snow Hill Island, where they erected a prefabricated hut measuring 4.1 by 6.4 meters (131⁄2 by 21 ft), unaware that it would be their home for the next two years. In early October Nordenskjöld and two others made a dog-sledge journey of 600 kilometers (373 miles) south to the coast of King Oscar II Land. In December, Nordenskjöld discovered the fossil remains of a giant penguin—the largest ever found—on nearby Seymour Island. However, ice conditions remained severe all through the summer, and when the sea froze on 18 February 1903 they knew they were trapped for at least another winter. They killed 400 penguins, 30 seals, and some skuas as supplementary rations, and even throughout their second winter kept detailed meteorological records.

Antarctic wintered in South Georgia, Tierra del Fuego, and the Falkland Islands, and turned south on 5 November 1902 to collect the Snow Hill Island party. After surveying part of the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula, the ship headed for the east coast but found the way blocked by heavy sea ice, so Gunnar Andersson, Toralf Grunden, and Lieutenant Samuel Duse were put ashore at Hope Bay on 29 December to establish a depot and try to reach Snow Hill Island over land.

Andersson and Larsen had prepared a contingency plan. Ideally, the ship and land parties would meet at Snow Hill Island, but if the ship arrived first and the land party had not arrived by 25 January, it would be assumed that the overland attempt had failed, and the ship would return to collect them at Hope Bay between 25 February and 10 March. Alternatively, if Antarctic had not reached Snow Hill Island by 10 February, the scientists and overlanders would return to Hope Bay and wait for the ship.

The three set off southward. Their only map was charted from the sea by James Clark Ross in 1843 so they were puzzled to find a channel crowded with icebergs where they expected to find land. They crossed the ice to Vega Island, but open water prevented them from reaching Snow Hill Island, so they returned to Hope Bay by 13 January and waited for Antarctic to arrive.

Meanwhile, Antarctic had pushed deep into the ice of Erebus and Terror Gulf, and on 10 January 1903 the ship underwent the first of several violent squeezes from the ice pack. The damaged and sinking vessel (holding a large collection of scientific samples) was abandoned on 12 February, and the 20 men—and the ship’s cat—crossed 40 kilometers (25 miles) of rough sea ice and patches of open water to Paulet Island. Arriving there on 28 February, they built a stone hut 7 by 10 meters (23 by 33 ft); its remains are still there. The flat basaltic rocks of the island were ideal building materials, and the hut even had two small windows. They had salvaged a ton of food from the ship’s stores, and they killed 1,100 penguins as a winter food supply—they intended to kill more, but the last of Paulet’s huge Adélie penguin colony quickly completed their molt and fled. Over the winter there was little to do, so meals and taking temperature readings became highlights of each day. On 7 June, seaman Ole Christian Wennersgaard died of a heart condition, and they had to store his body in a snowdrift until the ground thawed in spring and he could be buried.

The men at Snow Hill Island made several excursions and recorded hourly meteorological observations (which differed significantly from those of the first winter) but the three at Hope Bay had little but survival to occupy them. Realizing that the Antarctic would not return, they built a primitive stone hut with a tarpaulin roof, which could be warmed with a blubber stove to a relatively balmy few degrees below freezing. They took turns at cooking, and developed an elaborate ritual of formally thanking the cook after each meal. Andersson wrote of “the strong power that warm and honest friendship has, to proudly subdue the dark might of isolation and of extreme distress.” Assuming that by then Antarctic was lost and their whereabouts unknown, they started off on 29 September 1903 toward Snow Hill Island and the hope of rescue.

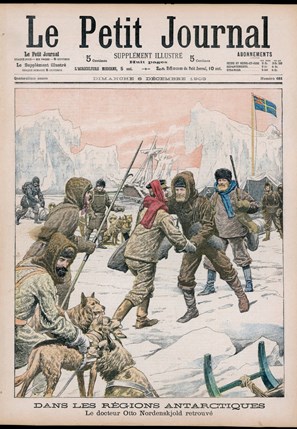

That same day, Nordenskjöld and Ole Jonassen set out on an excursion; they soon had to turn back, but began again on 4 October. By 12 October they had explored the whole west coast of James Ross Island and were traveling along the north coast of Vega Island. Far out on the ice they saw what they first took for penguins—and then realized were men. It was the three from Hope Bay, and the two parties met with “delirious eagerness” at a point they renamed Cape Well-met. They all made their way back to the Snow Hill Island hut to enjoy a celebratory banquet.

Meanwhile, several search and rescue expeditions were being prepared, including one on an Argentinian corvette, Uruguay, under the command of Lieutenant Julîan Irizar, Argentina’s naval attaché to Britain. Arriving at Seymour Island on 7 November 1903, Irizar’s crew found a boathook that Nordenskjöld had left on a signal cairn less than two weeks earlier. Investigating further, they spotted the nearby camp of two of Nordenskjöld’s men, fortuitously on hand to lead Irizar and one of his officers, Lieutenant Yalour, to the Snow Hill hut, arriving on 8 November. The two smaller of the three marooned parties were saved but it seemed that Antarctic and her crew were lost.

At about 10.30 that night the dogs started barking at six men approaching the hut. Miraculously, it was Captain Larsen and five others who could report that all but one of Antarctic’s crew had survived and were safely living on Paulet Island. Nordenskjöld wrote: “No pen can describe the joy of this first moment … when I saw amongst us these men, on whom I had only a few minutes before been thinking with feelings of the greatest despondency … We conducted the newcomers in triumph to the building.”

Larsen explained that they had come the long way round to Snow Hill Island. When the ice broke up in October, they had rowed to Hope Bay in a whaleboat, only to find that the three men stranded there had left for Snow Hill Island five weeks earlier. With a tent pole for a mast and the tarpaulin from Hope Bay as shelter, they crossed treacherous Erebus and Terror Gulf in their tiny craft, but had to walk the last 24 kilometers (15 miles) across solid sea ice.

The presence of the Uruguay solved Larsen’s last problem: how to rescue the 14 men he had left on Paulet Island. This group had been preparing for what appeared to be another inevitable year on the island, and had stockpiled 6,000 Adélie penguin eggs. One of the party, botanist Carl Skottsberg, wrote of the events of the evening of 11 November 1903—when he heard a sound in the night, he thought: “I must have been dreaming. The sound is repeated. It must be so … The boat is here! … I thump at the sleepers beside me: can’t you hear it is the boat … The shouts are so deafening that the penguins awake and join in the cries; the cat, quite out of her wits, runs round and round the walls of the room; everyone tries to be the first out of doors.”

The Swedish expeditioners were taken back to Buenos Aires, and from there to Malmö, Sweden. On the way they called into Hope Bay to pick up the rock samples and paleobotanical fossils that Andersson had collected. That was typical of an expedition that had carried out a full scientific program throughout a remarkable, harrowing adventure.

author: David McGonigal

Thinking of travelling to Antarctica?

Visit our Antarctic travel guide.

Heroic Age

- Douglas Mawson Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-14)

- Ernest Henry Shackleton British Antarctic Expedition (1907-09)

- Ernest Shackleton Imperial Transantarctic Expedition: 1914-17

- Ernest Shackleton The Quest (1920-1922)

- Ernest Shackleton The Ross Sea Party (1915-17)

- Jean-Baptiste-Etienne-Auguste Charcot French Antarctic Expeditions (1903-05)

- Jean-Baptiste-Etienne-Auguste Charcot French Antarctic Expeditions (1908-10)

- Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjöld Swedish South Polar Expedition: (1901-04)

- Roald Engelbreth Gravning Amundsen The Norwegian bid for the South Pole (1909-11)

- Robert Falcon Scott The last voyage (1910-12)

- Robert Falcon Scott – British National Antarctic Expedition (1901-04)

- Scott – The Other Expeditioners

Email Newsletter

Email Newsletter